In the eyes of civilization, the man in “Hut No.53” died nameless, without any set identity. His life, however, was not excluded from history and his death was a consequence of an ecological fatwa issued by leaders of the Brazilian dictatorship — who also managed to erase historical atrocities and genocide from the nation’s collective memory.

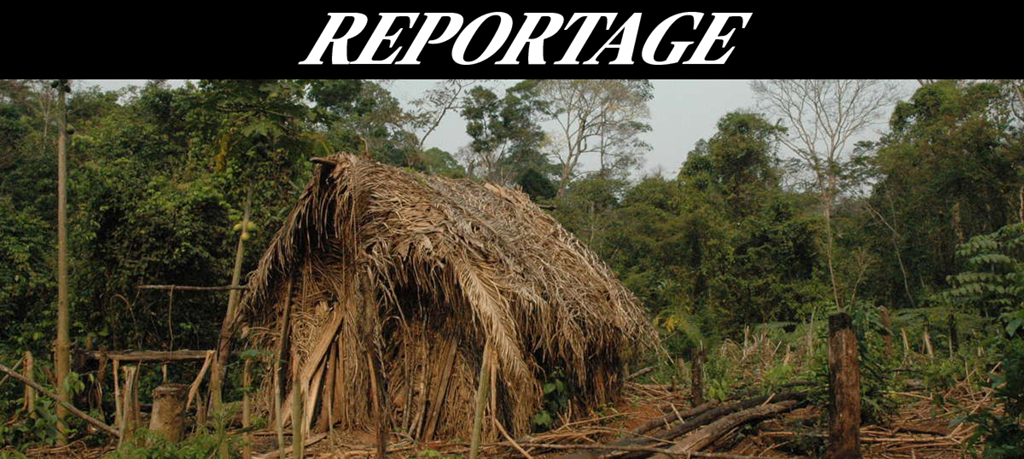

THE AMAZON | On 23 August 2022, a man was found dead lying in his hammock outside his hut somewhere in Tanaru Territory, in the Brazilian state Rondônia, close to the Bolivian border.

The man was not just anybody, and the discovery was made by Fundação Nacional do Índio (Funai), Brazil’s governmental protection agency of indigenous peoples’ affairs. The same federal body that had held the man under close watch ever since the late 1990s.

It was in 1998 that Funai first set out to seek contact with a man that rumors had it was living alone, somewhere off the beaten track in the tropical rainforest. The man made his living by digging holes to trap wild animals and he stayed in huts for short periods of time before abandoning them for new hunting grounds.

Funai estimated the man to be somewhere between 40 and 50 years old, although an autopsy confirmed the man to have been in his 60s.

Everywhere and nowhere

It was the solitude that struck those who were given the chance to observe the man at close range — a living example of an isolation that had sprung out of exterior circumstances rooted in Brazil’s military dictatorship and its colonizing programs in Rondônia during the 1970s and 1980s. The man knew perfectly well that he was the last of his tribe, just as he understood there was “another world” beyond the surrounding ocean of trees — yet he remained in solitude, one both chosen and forced upon him.

“His presence is everywhere and I can sense him watching our every move,” wrote Fiona Watson, a researcher and expert on indigenous affairs in Brazil, at Survival International, after visiting Tanaru Territory in 2004.

Everywhere and nowhere and always on the move in a jungle that is never silent — the Amazon has nonetheless lost yet another unique voice.

The man with many names

“Tanaru Man,” “The Man in the Hole,” “The World’s Most Lonesome Man.” There were plenty of names given to him. The man himself, though, never stated who he was, where he lived, his age, what language he spoke, or what dreams he nourished.

The reasons were many, but few were honorable for the bordering civilization that watched and studied him from afar, turning him into a spectacle and forced cast member of a Big Brother, set in a tiny patch of jungle under a desolate sky.

The man’s existence didn’t follow any prewritten script, but his destiny was nonetheless tied to an established narrative — civilization’s dismantling of the Amazon and subsequent cleansing of the guardians of the forest.

“He was, like all Indigenous peoples are, one of the best conservationists of the forests and their biodiversity which are so important in mitigating climate change,” says Fiona Watson.

Awaiting death

The man’s importance and way of reminding the world beyond his place of living and hunting should not be underestimated. His very existence embodied a physical hinderance for the expansion of cattle ranching in Rondônia, and he was subjected to at least one attempt of murder conducted by cattle ranchers who have surrounded Tanaru Territory with plows, roads, and cattle.

When death struck its final touch on the man it seemed as if its arrival was expected. According to Funai’s own report there were no signs of violence and all items and tools inside “Hut No.53” were left untouched.

The macaw feathers that covered his body in the hammock and on the ground next to him might have been a gesture to death itself — or perhaps to the other world that he knew were observing him. Whatever shape or form death arrived with, however, it mattered little as it completed an already launched genocide.

“We have lost the Last of his Tribe and with his death all their immense botanical, zoological and medicinal knowledge,” says Fiona Watson.

Ecological fatwa

The deceased man in “Hut No.53” in Rondônia was born at the same time as the military dictatorship was installed in Brazil, in 1964. After its power grab the military leadership adopted a colonizing policy in the Amazon that for the last man of an unknown tribe in Tanaru Territory meant a death sentence — an ecological fatwa issued by the Brazilian government. He was by no means alone in being issued this form of death sentence by the knights of civilization:

“His people were probably massacred by cattle ranchers who are invading the region at breakneck speed,” wrote Fiona Watson after her 2004 visit to Tanaru Territory.

Instead of running out into the margins of civilization — into the global periphery where the world’s indigenous peoples constitute 15 percent of those trapped in extreme poverty worldwide — the man held his ground. Year after year, decade after decade, in solitude while the edges of Tanaru Territory were trimmed down by bulldozers, slash and burn activities and chainsaws.

“I think he is a symbol of our rich human diversity which is so vital for the future of our planet,” says Fiona Watson.

A future whose sustainability either stands or falls with the Amazon.

A vanished Mega Lake in the African desert

The Amazon is not an isolated island. As everything else on this planet, the lush region in South America remains dependent on its surroundings. But “The Lung of the Earth” had never taken its current shape and form hadn’t it been for a lost lake at the edge of the Sahara Desert in northern Africa.

Lake Chad hasn’t always been an ebbing and emaciated body of water that currently struggles for oxygen in the wake of an ongoing climate crisis. Many thousands of years ago, things were different — Lake Chad then covered enormous stretches of land in modern-day Northern Africa and as the lake faded away its sediments and silts which rested on the lakebed — among them fossilized diatoms — were abandoned and left to dry and form layers of dust under a scorching sun.

The so called “Bodélé Depression” is considered one of the planet’s dustiest places, and its dust is swept away in frequent sandstorms that carry its fine-shaped load to the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, where minerals, salt, and diatoms in the freshwater of the former Mega-Lake Chad have fertilized the Amazon soil.

“Black earth”

The Amazon’s “terra preta,” or “black earth,” has remained hard to tame despite its far-flung assistance. Indigenous tribes started to cultivate plants in the Amazon around 6 000 BC, but various attempts using various techniques were needed to reap any harvests.

The tropical South American region is nonetheless home for large portions of the planet’s living beings, many only found here. The region also contributes to 25 percent of all ingredients in modern pharmaceuticals.

Just as external factors can contribute to the fertilization of the Amazon soil, external interests can also launch a destruction process that implodes the tropical body.

Chainsaws, religions, weapons

Prior to colonization around five million people inhabited the Amazon region. “The civilization” of the jungle would, however, rewrite all life and was launched as Spanish, Portuguese, French, and German expeditions started taming the mythical and resourceful rainforest basin.

Chainsaws, religions, and above all, weapons were essential in securing a sustaining presence in a world whose indigenous inhabitants regarded the European newcomers as intruders.

When the 1964 coup ‘d’état turned Brazil into a 20-year-lasting military dictatorship the very conditions of life were changed not only for trade unionists, journalists, women’s rights activists, and human rights defenders — the biggest change occurred in the Amazon.

Everything was executed as an economic, social, and political project along with an impactful slogan: “Brasil: Ame-o ou deixe-o.” Brazil: Love it or leave it.

“The Brazilian Miracle”

The confidence of the dictatorship was riding high, and the Brazilian economy experienced a bonanza — rooted in oil production, timber export, and cattle ranching — that was deemed “a miracle” and impressed immensely on Western economists, only soon to be disclosed as a financial house of cards centered around an unsustainable system for managing inflation through indexation of virtually all contracts and prices (“monetary correction”).

Above all, the economy rooted itself in an eternal facelift of “Brazil’s Green Desert” — turning the Amazon into a center of numerous infrastructure and colonizing programs. “Lands without people” would be turned into “lands for people without any land.”

Furthermore, military bases were built, as were hydrological dams, and roads. Most important, though, were the launch of various state-driven transmigration programs, where the allotting of lands to new settlers in desolated jungle pockets would dampen the risk of social uprisings in poverty-stricken urban outskirts.

Above all, the ruling military considered it a matter of efficient usage of an enormous and unexploited “terra incognita.” The Amazon was compared to an ox left in the barn instead of plowing the field and contributing to the farm’s survival.

The consequences of this working ox have meant disintegrated and forever lost ecosystems, cleared forests the size of Western European nations, and displaced indigenous tribes who instead made space for settlers, cattle ranchers, miners, and soy farmers.

“Tipping Point”

Since the integration of the Amazon during the military dictatorship the region has become an indispensable resource to the Brazilian economy. To halt the development before the rainforest reaches its “tipping point”, from where there’s no turning back, is therefore considered one of mankind’s primary measures to dampen the punch of the climate crisis.

“We’re playing an environmental Russian roulette,” Paulo Brando, a tropical ecologist at the University of California, told Nature.

The Brazilian rifle aimed at the “Lung of the Earth” consists of mainly three cartridges — the three “B’s,” the Bible, bullets, and beef, where Evangelical Church organizations actively seek to convert uncivilized heathens of the forest while weapon lobbyists and the cattle industry have continued to fire endless volleys against ecosystems and indigenous peoples despite the fall of the dictatorship, in 1985.

The Presidency of Jair Bolsonaro has assured a continuous — and accelerated — exploitation and colonization of the Amazon. Bolsonaro, and his political role models who steered the military junta, considers the Amazon as a “domestic forestry resource” — and its indigenous people should either accept integration into civilization or, simply, be removed.

The political chorus of the 2020s in Brazil is a haunting echo from the past: “Brasil: Ame-o ou deixe-o.” Love it or leave it.

“No illegal activities”

A Brazilian Truth Commission has stated that thousands of members of indigenous tribes perished during the military dictatorship due to confrontations, diseases, and arbitrary assassinations.

Despite the commission’s conclusions, the Brazilian military has maintained its stand that “no illegal activities” occurred in the Amazon — on the contrary, the army assisted in bringing oxygen to a green and lifeless desert.

Accusations of genocide has consequently and effectively been swept under the rug, and the military’s strategy of denial is essential to understand the widespread doubts that the Brazilian society upholds towards information regarding genocide and atrocities against indigenous peoples, says Rubens Valente, journalist and writer of “Os Fuzis e as Flechas” (“The Rifles and the Arrows”).

“Until today the Armed Forces have never apologized for any kind of apology for the deaths, diseases, loss of territories and other crimes committed against the indigenous people,” Rubens Valente told Folha de São Paulo, in 2020.

Ashes to ashes

The members of the unknown tribe in Tanaru Territory, in Rondônia, were among the thousands of people who were killed during the dictatorship’s colonization of the Amazon. The man who was found dead outside of “Hut No.53” somehow survived the ecological, financial, and military assaults and outlived the rest of his tribe members.

Now, as the last member of a tribe the outside world never got to know the name of has died, all that’s left is a hut — likely to decay and fulfill its place in a lifecycle to which all organic life in the Amazon is subordinate.

“His death is a wake-up call for us all to respect and value Indigenous peoples’ wisdom and knowledge and their right to be different,” says Fiona Watson, researcher at Survival International.

Dust to dust

In Tanaru Territory, in the groves that long housed a man who was labeled as “the world’s loneliest man,” two rivaling cycles approach their final encounter.

On one side, the industrialization of Nature, conducted by the Anthropocene Man, considered humankind’s birth right to cover all wilderness with civilization.

On the other, a cycle that evolved on a planet in the habitable zone many eons before any two-legged creature ever set foot in a tropical bower later to be named the Amazon.

“We must do all we can to prevent the silent, hidden genocides of other uncontacted tribes who are defending their forests against increasingly violent attacks and intrusions in Brazil and elsewhere,” concludes Fiona Watson.

* * *

Klas Lundström lived in the Brazilian Amazon in 2007 and 2008, where he reported on the soybean expansion and consequent social and environmental issues, along with child labor, migration, and illegal logging in Brazil, Colombia, and Peru.